A geological story

The Exhibition

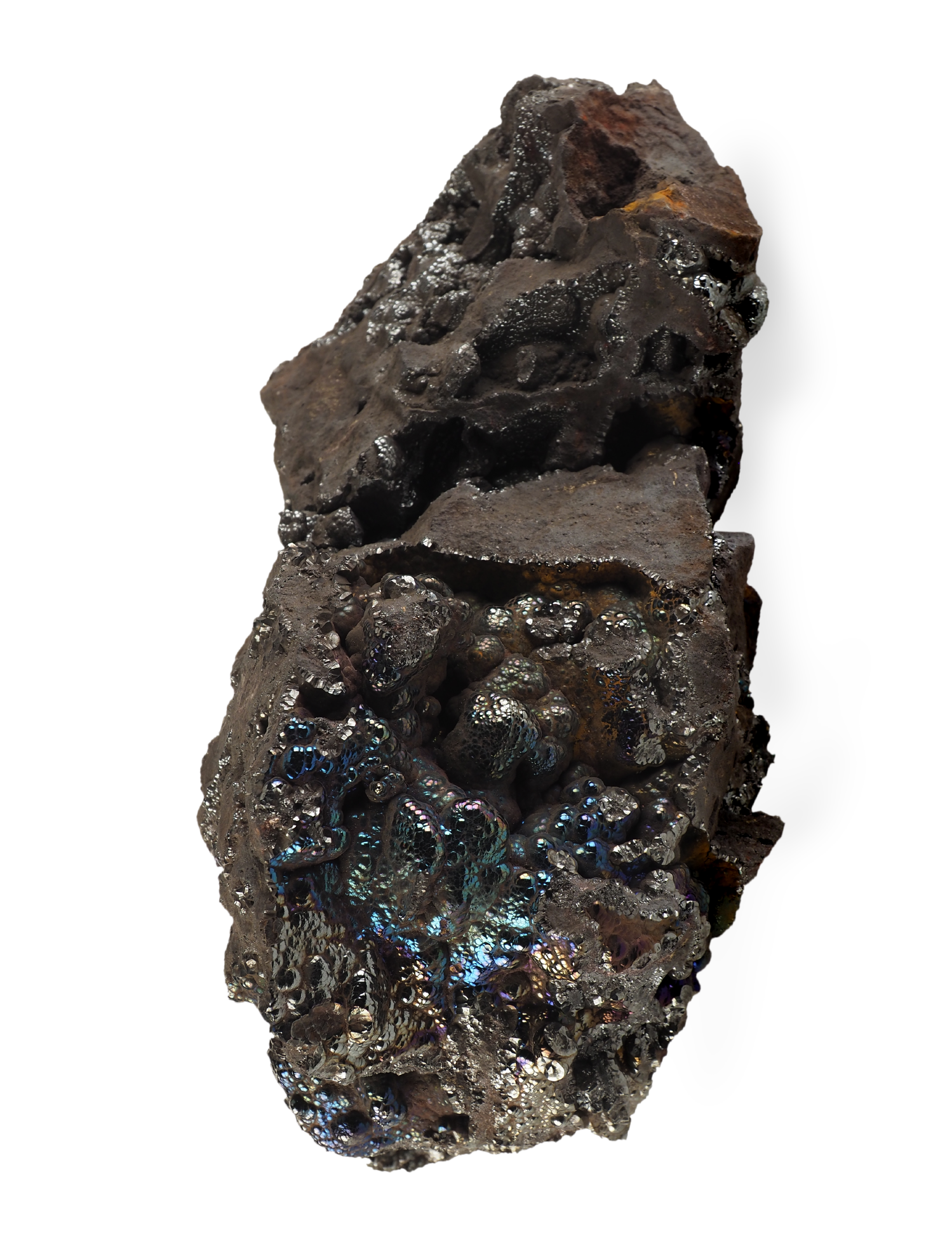

On 20th November 2024, we will launch the itinerant international exhibition “Moon Impact – a geological story” at the Thuringian University and State Library (ThULB), in Jena, Germany. The exhibition tells the story of the Giant impact and the Moon formation. Over almost 60 square meters of exhibition you will be able to learn about the formation of the solar system, about the Giant Impact that generated the proto lunar synestia, and about the ever-growing complexity of the mineral realm. You will admire distant proto-planetary disks, you will see animations of giant impacts and you will peek into the atomic secrets of the formation of the first atmosphere of the Earth. Apart from natural geological samples and meteorites, the exhibition features large-scale posters, translucent 3D window prints, movies and 3D printed models of the atoms in melts and volcanic gas bubbles stemming from atomistic simulations, and much more.

The idea behind

the exhibition

Moon Impact was born within the Impact research team of the CNRS (Paris). Led by Razvan Caracas, this team works on the formation of the Moon. These scientists want to share their discoveries with you and now they wish to guide your steps in the fascinating world of computer simulations and mineralogical analysis. The Moon Impact exhibition tells the story of the Giant Impact and of the Moon and the Earth that came after. It is a rediscovery of the history of our immediate universe through the prism of geology and mineralogy: formation of the solar system, formation of the Moon, diversification of the mineral world, interdependence of life on Earth and the presence of minerals, human influences on the mineral environment (Anthropocene, accumulation of plastic waste).

The IMPACT team studies the condensation of the Earth and the Moon from the protolunar disk, which formed in the aftermath of the giant impact. The team uses some of the largest computers across our continent to study how the atoms behave at extreme conditions of pressure and temperature. Numerical simulations model the melts, the gases, and the supercritical fluids that dominated the protolunar disk, they tell us what was the thermodynamic state of the disk, and how the early Earth and Moon condensed from that disk. The HIDDEN projects studies the hidden geochemical reservoirs of noble gases that lie deep inside the Earth.

The IMPACT project is financed by the European Research Council (ERC, via grant agreement no.681818, 2016/2021).

The HIDDEN project is financed by the Norwegian Science Foundation. (project no. 325567)

Razvan Caracas – Computational mineralogist CNRS (Paris) & PHAB (Oslo).

The IMPACT team members are: Mandy Bethkenhagen, Tim Bögels, Anais Kobsch, Zhi Li, Adrien Saurety, Natalia Solomatova, Xi Zhu

The HIDDEN team members are: Ana Anzulovic, Anne H. Davis, Sarah Figowy

©ESO | L.Calçada

About the exhibition

The exhibition in five steps

Formation of the solar system

Our solar system was born about 4.5 billion years ago inside a big molecular cloud that collapsed. This cloud formed a swirling disk of dust and gas with a star, the Sun, growing star in the middle. The gas and dust from the disk came together with the help of gravity, forming bigger objects. They kept growing into small planets, which we call planetesimals. While they kept revolving around the star in their orbits, they kept accumulating material until there was not much left in the disk. That is when the planets became fully formed. The formation of our solar system is the beginning of our geological story.

The giant impact

How did the Moon form? A planetesimal or a small planet, called Theia, most probably about the size of Mars, hit the protoEarth. The impact was giant, hence its name. Both Theia and the protoEarth disintegrated and evaporated forming a huge disk of hot debris, made of gas and liquids. As the disk, called a protolunar disk, started to cool, it condensed in a huge central ball of magma, surrounded by a donut-shaped cloud of hot gas. The magma sphere formed the Earth that cooled over a long time. The Moon coalesced in outer parts of the disk, gathering a large part of that donut cloud. Most of the light gases from the outskirts of the disk were lost into space, leaving behind a dry Moon. With no water, no carbon, no atmosphere, the Moon remained frozen in the same state as it formed, but preserving information dating all the way back to its formation, the protolunar disk, and the Giant Impact.

Geology of the Moon

Why is the Moon so different from the Earth? With no water, no carbon, no atmosphere, the Moon remained frozen in the same state as it formed. With geologic time it only cooled and its interior magma ocean slowly crystallized. Meteorite falls and cooling are the only geological activities, which continue even today. As the Moon cools, it contracts, and sometimes it cracks, provoking small seisms called moonquakes. The gentle shakes from the moonquakes are enough to erode the sides of the craters, which over billions of years slowly collapse. With such austere chemistry and a cold world, there are no reactions and no fluids at the surface and consequently no form of life could develop on the Moon. The only water found so far is traces of ice in the ever-frozen deep bottoms of the craters at the two poles, where sunlight never shines. And just because of its inert geology the Moon preserves information dating all the way back to its formation, the protolunar disk, and the Giant Impact

Mineral evolution

We all know that life evolved over time. As research advances, we progressively improve our understanding of the chemical and physical processes that led to the appearance and evolution of life. Minerals underwent something similar. Minerals did not “evolve” in the pure sense of the word, but rather they diversified. As time passed, the Earth turned out to be an active chemistry laboratory. As more and more chemical reactions took place, they led to a huge diversification of the mineral species. Under the action of heat and fluids and plate tectonics, over billions of years of chemical reactions, and strongly affected by the appearance and evolution of life, thousands of minerals have formed on our planet. There were 5616 documented and approved minerals as of July 2020. And the quest for new minerals continues!

What is the anthropocene ?

The presence of humans on the surface of our planet modified and continues to modify the geological environment. We modify not only the climate, though a constant flux of pollutants, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, but we also leave behind geological traces, which will be conserved for millions of years. Today we manufactured more synthetic materials than the total mass of living organisms on our planet. On the geologic time scale, some of these materials will disappear relatively quickly under the action of the environment, like oil derivatives and asphalt. Some will lurk around for many millions of years, like plastics. And some will simply remain in the geologic record, like glass, bricks and ceramics, and concrete.

till April 31st, 2025

November 20th, 2024 till April 31st, 2025

Practical Info

Monday – Friday: 8h – 22h

Saturday, : 10h – 20h

Sunday: 10h – 18h

The access to the exhibition is free of charge

Before your visit

Download our visit kit

GUIDE FOR GROWN-UPS

GUIDE FOR GROWN-UPS

Discover the small guide with the main elements of the exhibition

to accompany you during your visit.

GUIDE FOR CHILDREN

GUIDE FOR CHILDREN

Guided by the famous astronomer Vera Rubin, the children (6-12 years old)

will discover the main themes of the exhibition around amusing scientific anecdotes.

They will then be able to test their knowledge in small games.

Who's next?

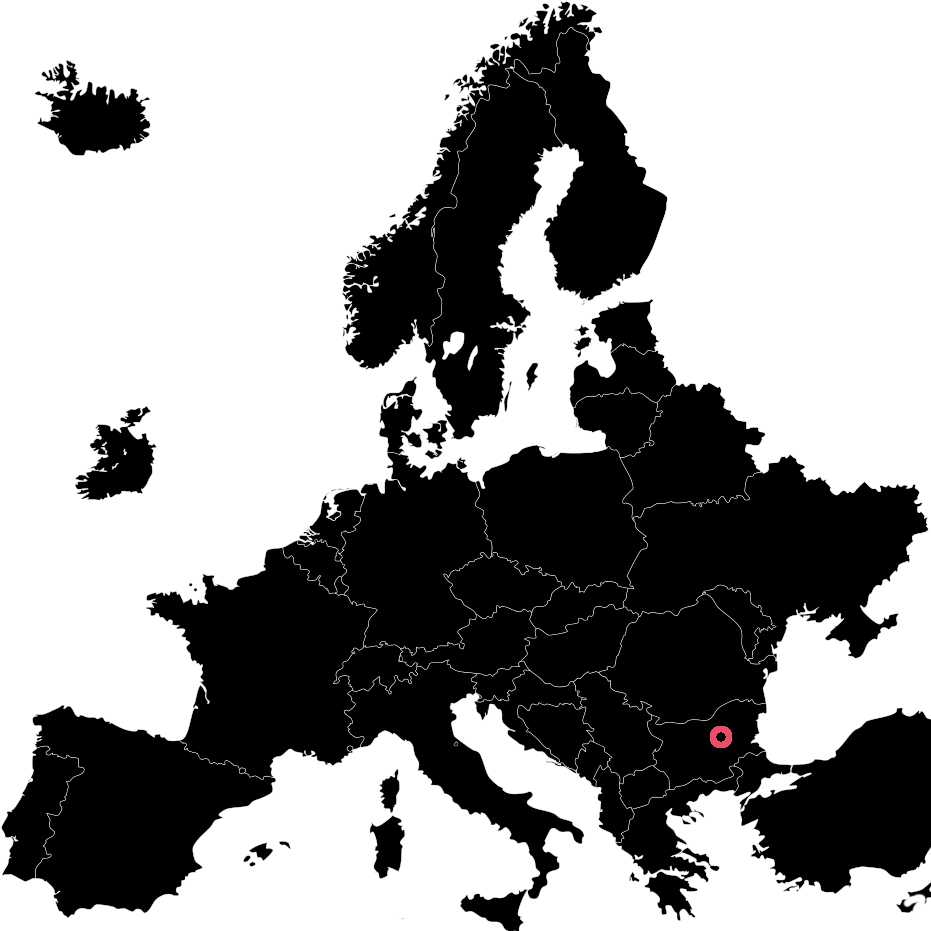

Itinerancy

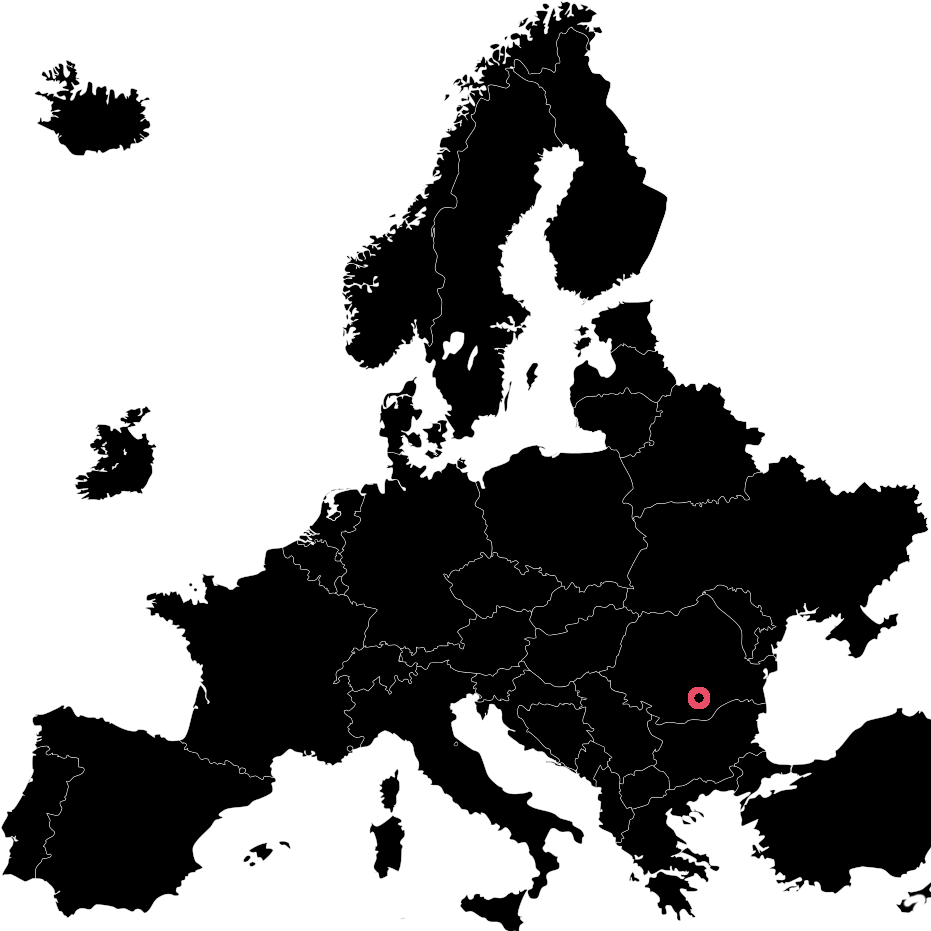

Brasov Art Museum

The museum is located in the downtown across the road from the central park. The National Gallery, the museum’s permanent exhibition, is housed in six rooms located on the first floor. The permanent exhibition highlights the local Transyvanian art environment throughout history. The exhibition includes artwork created by artists connected to Brașov, beginning with portraits of Saxon patricians and ending with post-war paintings.

National Museum of Natural History Grigore Antipa

The Grigore Antipa National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum, located in Bucharest, Romania. It was originally established as the National Museum of Natural History on 3 November 1834. It was renamed in 1933 after Grigore Antipa, who administered the museum for 51 years. He is the scientist who reorganized the museum in the new building, designed by the architect Grigore Cerchez and inaugurated by Carol I of Romania in 1908. The museum’s collection consists of over 2 million specimens. It is regarded as one of the most prestigious and well organized natural history museums in the world.

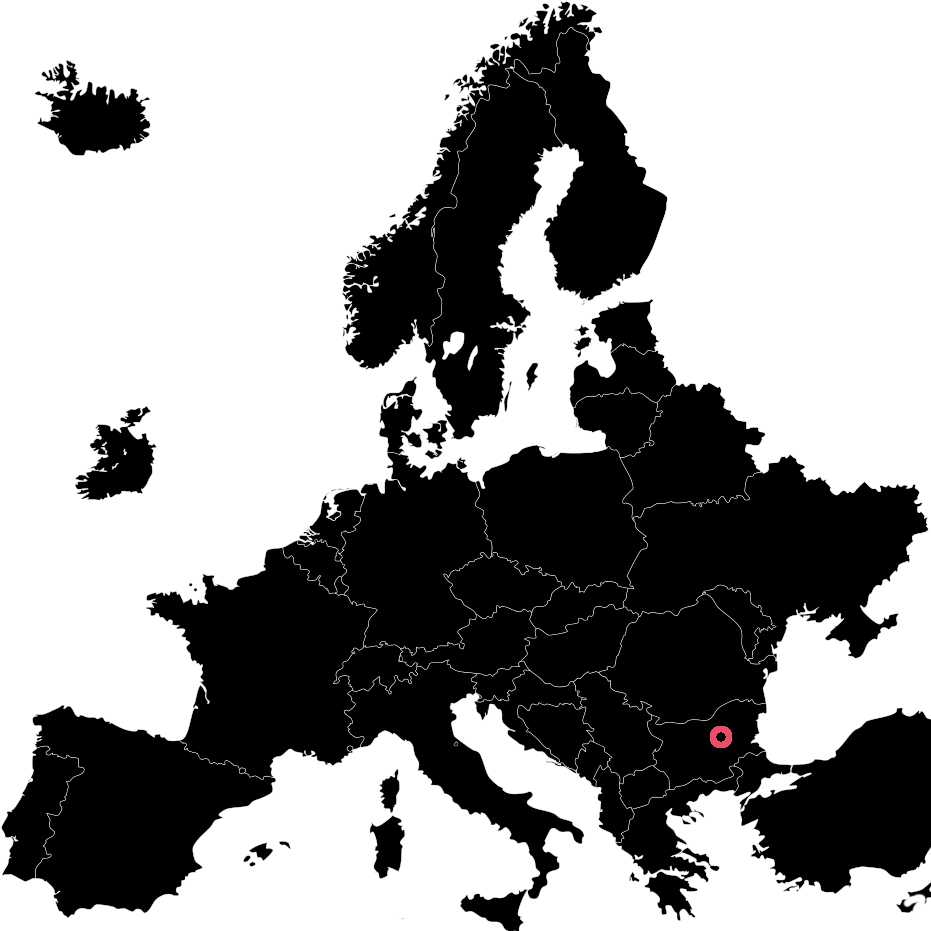

Earth and Man National Museum

The Earth and Man National Museum is a mineralogical museum in the centre of Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. It was founded on 30 December 1985 and opened for visitors on 19 June 1987. The museum is situated in a reconstructed and adapted historic building with an area of 4,000 m² constructed in the end of the 19th century (1896–1898). It has a number of exhibition halls, stock premises, laboratories, a video room and a conference room. Apart from its permanent expositions related to mineral diversity, the museum also often hosts exhibitions connected with various other topics as well as concerts of chamber music.

Regional Natural History Museum

The Regional Natural History Museum is a mineralogical museum in the centre of Plovidv, a major city in Bulgaria. The museum hosts permanent expositions related to botany and zoology.

Museum Mineralogia München

The Museum Reich der Kristalle is the publicly accessible part of the Mineralogischen Staatssammlung of Munich, Germany. It features explanations of mineralogical and crystallographic terms using models. It also showcases minerals local to Bavaria.Exhibition partners

About

Through the eyes of a geoscientist, discover the history of our planet from the formation of our solar system to today.

set up by the Impact project team from the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (CNRS/Université PAris Cité) and the Hidden project team from the Center for Planetary Habitability (PHAB/Unversity of Oslo).

Opening hours

Monday – Friday: 8h – 22h

Saturday, : 10h – 20h

Sunday: 10h – 18h

Bibliothekspl. 2

D-07743 Jena